RIPOSTE

by RIP RENSE

|

|

Chocolate,

Beethoven,

and The Beatles

"Suddenly a rainbow rose

and

spread across the land

Hung there while the Beatles sang

I want to hold your hand

What can you say?

Here tomorrow, gone today

Faith fades away

For idols with their feet of clay.

. ."

---Robert Hunter, “Aim at the Heart.”

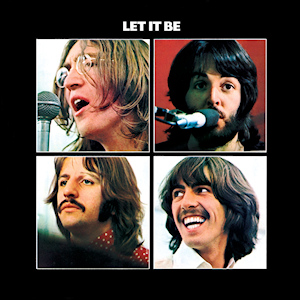

At last, I can look at

the dreary, stark, black-framed "Let it

Be" album cover without feeling crummy, without feeling like “this is the

one that got away,” without being put off by the fact that this is the

only Beatles album cover that shows the four guys divided, separated.

I don’t feel

good about it, mind you, but better.

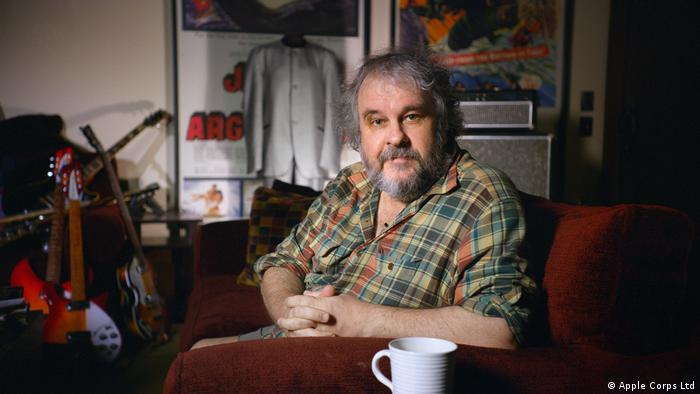

Thanks to Peter Jackson.

As is now well established, an enormous missing chunk of

Beatles history has been salvaged, contextualized, shined up---indeed,

revealed---repairing a project badly misunderstood for fifty years, and

patching a lot of long-broken hearts in the process. Melodramatic?

No, probably understated.

To grasp the importance of Jackson’s “The Beatles: Get

Back,” and why this extraordinary documentary is nearly eight hours long

(reportedly reduced from 18), one probably needs to have a little historical

perspective. To whit: The Beatles were a tectonic event in world history, nothing less. Right, not just

music history---world history. Without trying to do anything

other than sing and play instruments, without trying to do anything more

than make it big in Liverpool, or maybe even England, without trying to

do anything other than write some catchy tunes.

Or put it this way. Here you had the blundering,

murderous human race lurching along for a few thousand years, from

mayhem to war to genocide to plague to savior to mad dictator to A-bomb

to terrorism to eco-cide to double-cheeseburgers, and suddenly, along came

something. . .different. Really different. Something. . .uplifting.

Shockingly uplifting. You know, like chocolate. Or Beethoven. Not for nothing did

the pithy Grateful Dead songwriter Robert Hunter once write, “Suddenly a rainbow rose

and spread across the land / hung there while the Beatles sang ‘I Want

to Hold Your Hand.’”

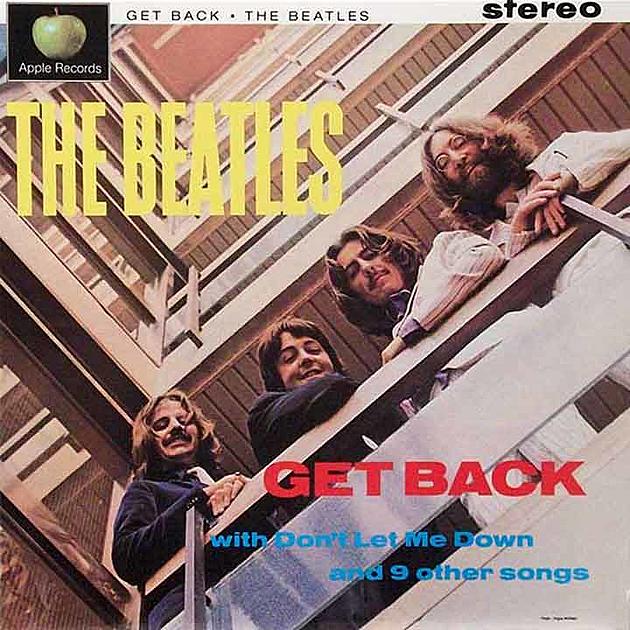

The final, bleak, black-framed "Let it Be" album cover---and

the album cover as originally intended when the project was

called "Get Back." |

They

weren’t just balm after the Kennedy assassination, though there was

that. They weren’t just a pop phenomenon, like Sinatra or Elvis, though

they were that. They were, oh, I don't know, the best possibilities of

human nature, maybe, appearing in a musical form. Wizards of

wonderment, magicians of muse, prophets of the possible. Carl Wilson

in the San Francisco Chronicle used the word, "epochal” to describe The

Beatles, and that is on target. Writer Rob Sheffield---born in 1966, the year

“Revolver” was released---tried to explain it in his Rolling Stone

piece about "Get Back:"

“That’s the mystery at the heart of Get Back: How is it

that we keep hearing ourselves in this music? People all over the world,

from all different generations and cultures, even though most of us

weren’t born back then? Why does the world keep dreaming the Beatles?

"They’re only the icons they are because the music was so majestically

good,” (Peter) Jackson told me. “There’s a joy in the songs that they

sang. In decades and decades to come, it will never be dulled. It will

never be suppressed. That joy, that infectious joy, is part of the human

psyche now.” And that joy is all over Get Back.”

Jackson

pegs it. The Beatles were an Ode to Joy, maybe the

greatest since Beethoven's 9th (and, as a lifelong informal

student of Beethoven, I do not say this lightly.) Tectonic? They were a

mirthquake.

But you have to

accept, I think, that joy is not merely

good feeling, exaltation, even plain old fun. Those lovely items are

short-lived. Imagine something that, every time you see it, think about,

hear it, read about it, experience it in any way at all, gives you a

kind of unfettered happiness, optimism, inspiration, reassurance, lift.

Automatically, instantly, Pavlovian-ly. The Beatles did this. They

didn’t mean to, they just did. They were absolutely electric. I mean,

ditch the Prozac---these guys were singing seratonin. I sometimes wonder if the happiness they engendered

amounted to measurable benefit to humanity and ecosystem---no, really. Happy people

are constructive people, after all. Fact: crime across

the country went way down when the fellows debuted on The Ed Sullivan

Show Feb. 9, 1964. (Note: 72 million watched that night; by

contrast---even with social media---the Grammies fetch about eight

million.)

As if that weren't

enough, John, Paul, George, and Ringo also conveyed, overtly and

implicitly, if I may put it crudely, “To hell with all bullshit, create beauty

instead"---by doing it, themselves. They lived this attitude,

exuded it, sang it; they

were (and are) monuments to free-spirited elan---inspiring by example, even if

unintended. After all, they'd made it to the "toppermost of the

poppermost," as they used to say, simply by being true to their art, and one

another. No, they didn't "break all the rules," as the cliche

goes---they simply ignored them, winked at them ("rattle your jewelry,"

Lennon smilingly told the Royal Variety audience Nov. 4, 1963), and went

their own all you need is love way.

Which brings up this celebrated, much-written-about aspect: so many of their songs were either subtly or anthemically about.

. .love. The only word is love. . .All you need is

love. . . Make love singing songs. . .The love that's shining all around

you. . .Love was such an easy game to play. . .The love you take is equal to the love you make.

. .She loves you yeah yeah yeah. . .Love and beauty---well now, that's

rather serious joy, ever in short

supply, and these are things that The Beatles manufactured in seemingly limitless

abundance, in effervescent song after album after song after movie. Small wonder people went nuts over them. Small

wonder the press glibly diagnosed "Beatlemania." Small

wonder Harrison declared, in retrospect, "They used us as an

excuse to go mad, the world did, and then blamed it on us."

It was a fine madness,

though. And yes, The Beatles get the blame. As

Jackson's documentary reminds in restored footage that is gloriously, almost

painfully alive, that madness is still a fine thing. Get Back?

The Beatles, because of this astonishing documentary, are back,

probably more popular than ever. These boys will forever live---more

alive than most living people---on these eight hours of film shot by

Michael Lindsay-Hogg in 1969, edited by Jackson in 2020-21. There will

be---already has been---no end to the study and rumination over this

unexpected material.

Oh, the break-up? The thing that grabbed your spiritual

ectoplasm and shoved it into a shredder? It will be eternally tragic,

traumatic, to those who lived through it, and yet---and this approaches

miraculous---it is now somewhat less so because of Jackson.

Specifically, because of what we learn while feasting upon those eight

hours from January, 1969. . .

In a way, “The Beatles: Get Back” is like meeting the group for the

first time, so revelatory it is of their personalities, quirks,

vulnerabilities, relationships, mercurial method of working. It is

easily the most important, candid document of the group extant,

certainly the only one to show them in the act of creation (unless you

count the short studio “Hey Jude” footage of 1968.) Did they pose? Mug?

Censor their behavior? Play to the cameras? Surprisingly little. These

guys were so used to relentless cameras in their lives, I don’t think

they adjusted their essential behavior for the lens. And, as has now

been unanimously agreed to in an avalanche of articles, these

legendarily acrimonious sessions were not, repeat not, so acrimonious.

These four young

friends of

intelligence, wit, aplomb, introspection, originality,

music---and, by '69, mythic life experience ---were not, as had been

universally thought, bickering themselves into breaking up, devolving

into the worst, pettiest, sordid ego-driven ugliness. No. They were, it

turns out, trying heroically to keep Beatles machinery

functioning---despite newfound personal priorities, and

too-much-on-the-plate pressures such as marriage, fame, and running their own

Utopian arts company, Apple Corps., with zero business experience or

acumen.

Yes, here they were---the

most loved and emotionally depended-upon humans alive, keenly aware of

that impossible, unwanted responsibility, yet trying to

preserve their storied collaboration. Never mind no Brian Epstein, who

elicited a unanimous group respect that was part of Beatles glue.

Never mind Lennon’s waning, always mercurial Beatles energies siphoned

off by Yoko Ono’s avant-garde posing, Svengali influence, and fondness

for snorting heroin. Never mind brilliant Harrison’s well-earned

resentment over playing second fiddle (well, guitar.) Never mind the group

having offended and alienated producer George Martin to the extent that

he appointed a surrogate, Glyn Johns, to take over. Never mind all these

obstacles, and more, because, as Jackson adroitly, journalistically

shows us, in the end, these wonderful beings called Beatles were as

triumphant and magnificent as aging Muhammad Ali rising to the occasion

of decking the behemoth, George Foreman.

Beatles songs are forever

tritely quoted to illustrate life, and that's a reflection of how

applicable they are to human experience, so here's one more: With “The

Beatles: Get Back,” Jackson has taken a sad song and made it better.

In short, this

is not your average cool awesome “rock doc” about your fave

band, kiddies, with lots of talking heads interrupting old footage with

platitudes and superlatives. Really, those sorts of documentaries are

not documentaries at all. They’re hagiographic public relations reels

for fans, edited for marketing/ demographics-calculated profit. “The Beatles: Get

Back” must be the most intimate look at any band (possibly any composer) in the act of inventing

music, ever. Jackson has, with skill and panache, limned and couched 60

hours of footage into a boffo eight-hour adventure, really a hero’s

journey. The best in us overcomes the worst in us, more or less. We

can work it out. Joseph Campbell, the late professor of comparative

mythology and author of "The Hero With a Thousand Faces," would approve.

No, Harrison was not

merely dour and disinterested, as previously believed. Ringo was not

merely depressed or sullen, as previously believed. McCartney was not

merely intractably overbearing, as previously believed. Lennon was not

merely sarcastic, ambivalent, dismissive, as previously believed. They

were, despite manifesting all of these qualities at times, striving to

work together, to create together, to be together. They had a little

help from their friend, the ebullient Billy Preston, who sealed the

deal, but it was the fraternal forgiveness and love among these four that

saved the day. This is profoundly moving.

Jackson worked with the

legendary “Get Back/Let it Be” session footage (missing for many

years---finally

recovered

by Interpol!) shot by Michael Lindsay-Hogg, often having to

painstakingly synch it up with audio tracks, and then assess it, in toto, like a reporter, not just a filmmaker. He

went in with an open mind to see what he could see, to see what

narrative the film organically held---not the story he could wring from it. Never

mind the angle pervading the it-is-to-weep original 1970 Lindsay-Hogg “Let it

Be” film (whether intended, as Lindsay-Hogg denies, or not): that The

Beatles were falling apart. Lo and behold, Jackson found a different

arc, and a more accurate one---that of the band doggedly surmounting

obstacles to stay together---in the process, creating a film even more honest than “Let

it Be” (which, unlike “Get Back,” did not show Harrison quitting the

band.) The first installment of “Get Back” alone is even more

distressing than the entire “Let it Be" film. By part three, you are just

thrilling to the increasingly charged concert on the Apple rooftop.

Fists clenched, heart racing, you are thinking, they did it!

The great Peter Jackson. |

Many excellent

pieces

in the documentary’s wake have summarized the dozens of piquant moments

in the thing, from the secretly taped Lennon/McCartney heart-to-heart. .

.to Preston’s surprise catalyzing arrival. . .to the astonishing

birth of the song, “Get Back,” from McCartney’s lost-in-a-trance bass

jam. . .to Harrison’s dismissing a proposed live performance on an ocean

liner as “insane”. . .to Ringo dabbling in his own song ideas about

either North or South Carolina (he didn’t specify) and octopi. While

they are all utterly remarkable, nothing was more gripping than that

dynamic-defining conversation between John and Paul, caught, like

something out of a “Pink Panther” movie, by Michael "J. Edgar"

Lindsay-Hogg's secret microphone in a lunchroom bouquet.

All the things that were

long suspected and conjectured by countless writers over the years were,

thanks to the bugged bouquet, kind of swept aside. It is astonishing how

self-aware Lennon and McCartney were. Those of us who, way-back-when,

fantasized about sitting down with the fracturing band, and saying,

“Now, if you can just understand thus-and-such, you’ll see that . . .”

can relax. They knew. Lennon knew he was struggling with wanting

to pursue other (Yoko) interests. Paul is aware that his often

overbearing music-direction---long accepted by the group---had worn out

its welcome, as "the lads" had grown older, more confident, capable.

Yes, he still stings from his musical ideas being taken as insults, yet

he humbly acknowledges Lennon's criticism that some McCartney musical

direction damaged or ruined his songs. ("Across the Universe," which was

very precious to Lennon, is an obvious example, as the two girls

recruited by Paul to sing high harmony vocals on the initial version

were at odds with the gravitas of the piece, in Lennon's mind.) And

then, in an exchange so casually candid as to introduce jaws to floors,

the two former boyhood friends and peerlessly intuitive collaborators established,

or re-established, group hierarchy:

“I’ll tell you what,” says McCartney. “What I think. . .the

main thing is this: you have always been boss. Now, I’ve been sort of

secondary boss.”

What’s more, you can feel Lennon’s alarm, and outright guilt,

over the two of them having kept Harrison's songwriting at token level: “It’s like George said, he didn’t get enough

satisfaction anymore because of the compromise he had to make to be

together. It’s a festering wound.”

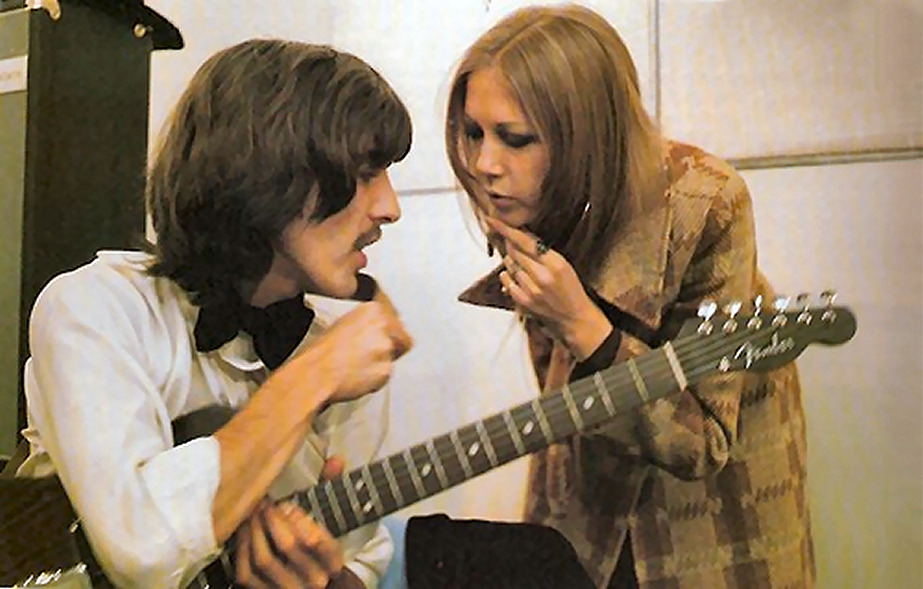

Yet evidence of

compromise is everywhere: Harrison famously quits (his departure, as is

seldom reported, occurred during a brief period where his wife,

Pattie, had left

him over an alleged affair---which might well have fed his impulsive

Beatles resignation), yet

is cajoled and persuaded into returning by the other three in two

separate meetings over the course of a week---in exchange for dropping

the ideas of performing in an amphitheater in Sabratha, Libya, and

turning the film into a television special. (Never mind John’s

characteristically impulsive quip about hiring Eric Clapton.) And George then

becomes heroic---enthusiastically contributing to the proceedings, despite still having

only a couple of songs accepted. His guitar playing is inspired. The

layout of the Paul song, “Get Back”---gasp---was entirely

George’s idea! (As well as part of “Let it Be.”) Distracted Lennon

manages to occasionally stop the manic Marx Brothers-meets-Dali stream

of consciousness quip-fest enough to do some real old-fashioned

John-and-Paul work. And hell, it is John who

solves the problem of how to arrange another Paul song: “Two of

Us,” suggesting a change to acoustic guitars (with Harrison deftly solving the

briefly discussed problem of no bass, by simply playing that

unforgettable, essential loping bassline on his guitar.) As for McCartney, he

unselfishly tamps down his domineering musical ways, and allows songs to

take shape as a group effort (a much more productive route, as it turns

out) even if it results in him becoming visibly bemused. Ringo? He rolls

his eyes at being told what to do at one point, but at another, he

gladly accepts Paul’s idea of the wonderful verse cymbal-tapping for

“Don’t Let Me Down.”

Harrison and wife, Pattie, after he rejoined the group.

His departure, as is not widely reported, came during a

brief marital separation. |

And what

about that “birth of ‘Get Back’" moment? McCartney is

strumming the bass, like a guitar, looking mesmerized, when the

central riff of the song appears from nowhere. He keeps working it. Ringo, watching and listening carefully, nods. Harrison takes note, pays

attention. They all realize that there is a big fish on the line, and

get to work on reeling it in. In the end, this song---long thought to be

a McCartney work---is revealed as a total group collaboration, from Ringo's snare triplets to Lennon's ingenious lead guitar to

Harrison's chop-chop rhythm comping. As Paul remembered in an old Beatles sheet

music book, "We were sitting in the studio and we made it up out of thin

air. . .we started to write words there and then. . .when we finished

it, we recorded it at Apple Studios and made it into a song to

roller-coast by.”

Then there is Preston, appearing

like something scripted. When the band regrouped in the new,

not-quite-ready Apple basement studio, abandoning the impersonal,

massive soundstage at Twickenham, everything improved by leaps and

bounds. But when old friend Preston (whom they met in the early days on

stage in Hamburg, Germany) just happens by (captured on film), it is

galvanizing. Billy sits down and begins playing as if he

already knew all the songs, and had always been in the band. It's

gasp-worthy. The others are clearly over the moon. It's like Mr. Hyde

transformed back into Dr. Beatles.

Oh, where have you been, Billy boy, Billy boy. . .No surprise at

all that Lennon actually suggested making him a Beatle.

Easily the most moving

moment of the entire documentary, for my money, is the day that neither

Harrison nor Lennon showed up for work,

Jan. 13. Paul, his wife, Linda, Ringo, director Lindsay-Hogg, de facto

producer Johns, redoubtable Beatles right-hand-man Mal Evans and a couple

of aides sit glumly in Twickenham,

discussing the

previous day's meeting at Ringo's home, which failed to bring

Harrison back into the fold (and which found Yoko Ono more or less

usurping Lennon's position, speaking almost entirely for him.) Time

passes with no Lennon, until all begin to genuinely fear that this is

it---the man behind the curtain has shown himself; the group has really fallen apart. Silence kicks in. You have to look

closely, but McCartney is clearly seen stifling a huge, heaving, sobbing

breakdown. It's shocking to witness.

This is how much Paul loved John

Lennon, and this is how much he loved The Beatles. It is Jackson's eye

that allowed the world to see it.

|

Billy arrives!

Billy arrives! |

How volatile the

situation was with these four extreme personalities, three of which had been

together since they were in mid-teens, and yet how stunning it was

to see them jettison differences, and shift into infectious high

spirits whenever the music started to click. To be able to witness all

of this, after having only had a sliver of information available in the

original "Let it Be" movie, or bootleg albums, is an emotionally

demanding exercise in fascination, frustration, elation---ultimately

leaving you feeling like Billy P. just happened to drop by your house, and

began playing for you.

The lurking

specter (aside from Phil Spector, who didn't show up for almost a

year to create the wildly uneven "Let it Be" album from the sessions) is, yes, the knowledge that eventually the group did split

up---but not until March, 1970, and after the

mountain-climb of “Abbey Road” (originally to have been called

“Everest,” after engineer Geoff Emerick’s cigarettes, possibly also for

the feat accomplished.) Knowing---seeing---that they tried hard to keep Beatling

during "Get Back"---takes some of the sting out of the “Of all sad words of

tongue and pen, the saddest are these: it might have been” factor.

And so this

Byzantine saga turns out, to everyone’s surprise---including Ringo and Paul,

who have praised the documentary to the hilt---to be a success story.

After the disastrous week of trying to invent songs in the chilly,

gigantic Twickenham soundstage---about as hospitable a working

environment as an Amazon shipping center---in the early morning, no

less---after George quits the group. . .after Lennon does not show up

for work, leaving McCartney quelling those full-blown

sobs. . .the band gets back to where it once belonged.

It's a victory of spirit, a victory of belief

in human

cooperation, an affirmation of faith and friendship, and the notion that

the sum is greater than the parts. (Quite a lesson for the present

socially separatist day.)

McCartney's cheerleading speech about his mates being at their best when

their backs are against the wall is borne out, in living color. That's

the point, really: all these events can now be seen, after half a

century of rumor, supposition, assumption, and an overriding

belief that the sessions were a grim failure. Jackson understood

this, saw the epic tale taking place, and, with empathy, an eye

for subtlety, and deep Beatles knowledge, produced a riveting

music-drama of anguish, suspense, surprise. You can’t take your eyes off it, all eight hours. (Thank goodness the job didn’t

go to Ron Howard, whose “The Beatles Live” could not have been more

predictable, shallow, and neglectful in portraying the evolution of the

group into a great live act.)

One more point that comes across like a banner headline: the project,

which was McCartney’s idea, bordered on insane in the

first place. Write, record, and perform a slew of entirely new songs in

three weeks? What other group might have even tried such a thing? And

this came only two months after the release of the band's highly

contentious, occasionally brilliant "white album,” in November,

1968---as well as Lennon's daffy, or at least self-indulgent "Two

Virgins" disc with Ono, with the infamous nudie cover banned around the

world.

There had been a Christmas break, but then taskmaster McCartney was

right back on the phone to his compadres, as always, selling them on

this new venture, an obvious attempt to reunite, reboot. One assumes he

thought the pressure might be inspiring, and in a way, despite the

initial crash-and-burn at Twickenham, he turned out to be right. The proof? Lennon

declaring, “Fuck it. Let’s do it,” as they stood hesitantly at the door

to the Apple rooftop, still unsure about whether to go through with the

now legendary live performance.

And there they

stood on that gray 45-degree day, on a makeshift wooden stage above

London, rediscovering their prowess, power, art. When the bobbies

arrived to politely announce that the band would be arrested for "disturbing

the peace," I laughed. No phenomenon has

brought more peace (joy, happiness, cooperation, love) to the world than

The Beatles. "Disturbing the peace?" With "Get Back," they were creating it.

PRINTER-FRIENDLY VERSION

MORE "GET BACK" RENSE COVERAGE:

DISNEY

MICKEY MOUSES

"THE BEATLES GET BACK" DVD/BLU-RAY

REVIEW:

LET IT BE---

Six different albums, seven different producers. . .one opinion

A Slightly Personal History of the "Get

Back/Let it Be" Project

Sidebars:

exONOrated?. . .Was the Harrison affair due to an affair?. . .more. . .

"Get

Back/Let it Be" rights and wrongs!

How many "Get Back/Let it Be" covers

are there? This many!

Get Back coverage, front page

BACK TO PAGE ONE |

![]() Get

Back/Let it Be

Get

Back/Let it Be