A Slightly Personal History of the "Get

Back/Let it Be" Project

by Rip Rense

|

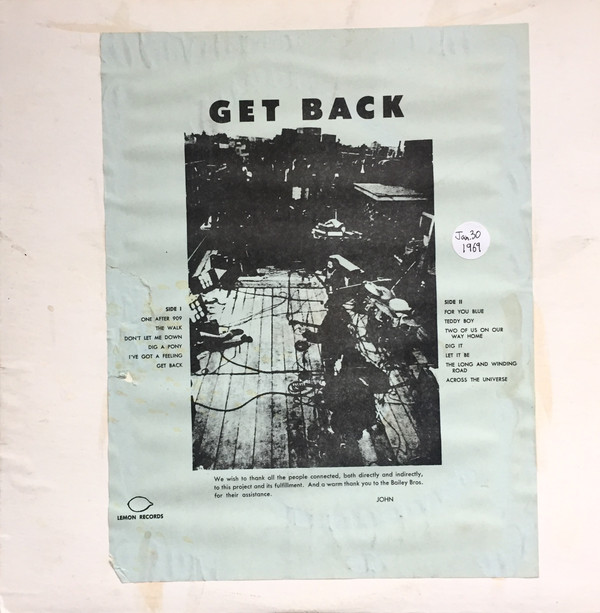

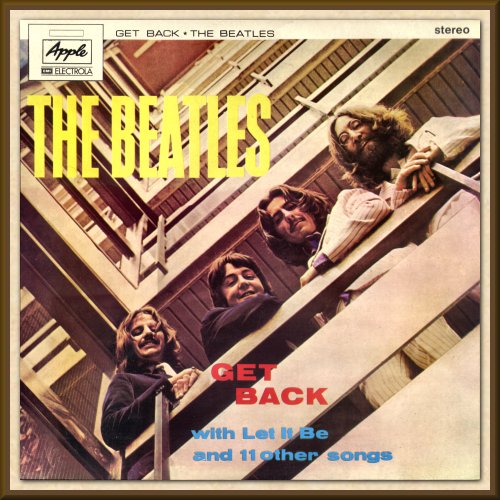

The original "Get Back" bootleg, on "Lemon Records,"

that appeared in September, 1969, eight months

before "Let it Be." |

There must be an adage along the lines

of: one little thing goes wrong, a million follow. You

know, one mouse nibbles, the whole cheese goes to hell.

Something like that.

That is more or less the

story of the “Get Back/Let it Be” project. In this case, the

“one little thing” was George Martin bowing out as supervising

producer, I would argue, and appointing young Glyn Johns to take over. Had Martin remained, and the band followed his

solid guidance, there likely would have been: a fine new album,

a TV special about its making, and at least one live concert.

Or, at minimum, a fine

new album.

Instead there have been

four albums of the sessions---five if you include the 2009 remaster---countless bootlegs, one largely

depressing motion picture, a brief but grand performance on a

rooftop, and, at long long long last, a brilliant

documentary: “The Beatles: Get Back.” (Score one for the

cheese.)

Only original fans,

probably, can appreciate exactly how involved, tangled, criminal

(literally), exasperating, and downright cuckoo the whole “Get

Back/Let it Be” saga is, because they lived through it. Over

five decades. Talk about: you and

I have memories longer than the road that stretches out ahead. .

.

As for the rest of

you, well, parting the pot-scented swirling mists of time. . .

When I first heard of the

project---through this-or-that friend or magazine, probably in

January or February of 1969---I perked up. Hell, the Vietnam,

assassination-weary world perked up. The Beatles were going to

play and record live, with no overdubs, all new songs, and a show

(or even tour?) to follow---after having seemingly retired to

the recording studio in 1966. The return of Christ, to recall

Lennon’s infamous controversy, might not have been competitive.

Suddenly, there they were

on the tube again---the first time since scruffy “new Beatles”

appeared via Michael Lindsay-Hogg’s filmed performances of “Hey

Jude/Revolution” in the summer of ’68. Promo films of their

terrific new single, “Get Back” and “Don’t Let Me Down,”

performed whimsically on their Apple HQ rooftop, showed up

on, of all things improbable, The Glen Campbell Show,

April 30, 1969. (Also filmed by Lindsay-Hogg.) The music was

spare, unlike any previous Beatles work, signaling yet another

vast stylistic change from this most chameleon of musical

aggregations. Was this country? Blues? Rock? Country-rock-blues?

Would the whole forthcoming album be like this? Was this the new

new Beatles? And who on earth was the antic keyboardist

credited on the single, and playing on the roof with them, Billy

Preston? Well, the coming album would answer all these

questions. . .

But then. .

.nothing.

There was no new

album, following up on the single. It didn’t turn up in the bins of The

House of Sight and Sound or

Wallach’s Music City---the big L.A. chains at

the time (Licorice Pizza opened in '69, and Tower and The Wherehouse came

along about a year later.) Instead, along came another handsome

black-sleeved “The Beatles on Apple” single, only a month later, and it was

an odd one: the slapdash “The Ballad of John and Yoko,” reportedly featuring

only John and Paul, with a B-side of Harrison’s peculiar shuffle, “Old Brown

Shoe.”

And again. . .not another

peep, no sign of an album.

The mystery remained for

five long months, only to be compounded in late September of ’69, when, at

long last, a brand new Beatles album did appear, but not the reported “Get

Back,” and with little fanfare. I stumbled across a British import pressing

of it in The House of Sight and Sound in Marina del Rey, California, one

afternoon after 11th grade, just sitting there quietly in the bin

marked "The Beatles," no trumpets, no parades, no dancing donkeys. (I

literally ran two miles home, stole $3.50 in change from my parents’

bedroom, ran back to buy it just before closing time.) This, of course, was

the superb, polished masterpiece, “Abbey Road,” a more-than-welcome

contribution to a wounded world.

So. . .

|

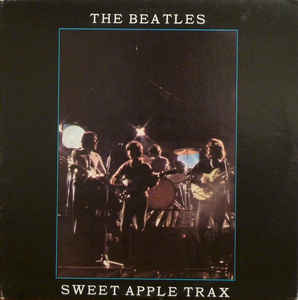

"Sweet Apple Trax," the first major bootleg of "Get Back/Let it

Be" rehearsals. Two LPs. |

Had “Get Back” been

junked? Had it even been recorded? None of the songs on the previous two

singles were on "Abbey Road," and there was no word about a “Get Back”

session LP in the offing. Then, in 1970, something downright freaky

happened---a full year after the project reportedly took place. No, another

new Beatles album did not slip quietly into stores---rather, it slipped

quietly into swap meets, “head shops,” radio stations, the backs of used

bookstores.

It seemed that acetates

of early versions of most of the “Get Back” songs, plus jam-snippets such as

“The Walk” and “Dig It”---all supposedly owned by Lennon---had leaked,

whether accidentally or deliberately, to WBCN in Boston, which promptly

played them on the air. The date was Sept. 22. Tape recorders whirred.

Suddenly, somewhere around 20,000 crudely packaged albums, referred to as

bootlegs---taken from the WBCN radio broadcast (and other

stations)---began circulating with various titles: “Kum Back,” “Get Back to

Toronto,” and “Get Back.” White covers stamped with titles, or with crudely printed

one-sheet pasted on.

One afternoon, as I rode a city

bus home from Venice High School, in Los Angeles, this nice neighbor kid

asked me if I’d heard the new Beatles album. I thought he meant

“Abbey Road." No, no, he said---it was kind of a secret message from

The Beatles, a secret album. At sixteen, I certainly had no

idea what this meant, but I figured The Beatles were up to something weird

and wonderful, as usual. Well, the kid kindly loaned me his copy of the

disc, “Get Back,” on “Lemon Records,” and for a few weeks I played it

several times a day, in utter bafflement. The songs mostly sounded

unfinished, or had false starts, even (gasp) partially completed lyrics, and

the sound quality was less than optimum. The songs were good---this was The

Beatles, after all---but. . .kind of informal, different. After the

high-tech sheen of “Abbey Road,” this was jarring---and a puzzle that was

not (partially) solved until March 1, 1970---when, suddenly, there were The

Beatles again, appearing on, of all things full-circle, The Ed Sullivan

Show! Shades of 1964! Except these were the pre-“Abbey Road” Beatles,

which was discombobulating, and they appeared via filmed performances of

two new tunes,“Two of Us” and “Let it Be”---year-old songs, embryonic

versions of which had appeared on the bootlegs!

Everyone wondered: now

was the “Get Back” album finally coming out?

Before that

question was answered, however, there came a 9.0 culture quake. Paul had

left The Beatles. (We know now that Lennon had left the group the preceding

fall, but had asked the other Beatles to keep it quiet.) As I wrote, decades

later, in my roman a clef novel about growing up, “The Oaks:”

Everything was different now, less. The world was hollow. It

was as if all the grass had retracted, or all dogs and cats had run away, as

if basketball had never been invented, or poetry, or ice cream, or

primroses. How could you go about business as usual? The wedding ring

bounced and rolled into the sewer, the composer died before the symphony was

finished, the Mona Lisa frowned, the cake fell, the house burned down.

Everything was false, echoey. Beethoven a plagiarist, your mother

moonlighted as a hooker, the dog didn’t really like chasing the ball, the

rainbow went black-and-white, Muhammad Ali turned out to be a woman.

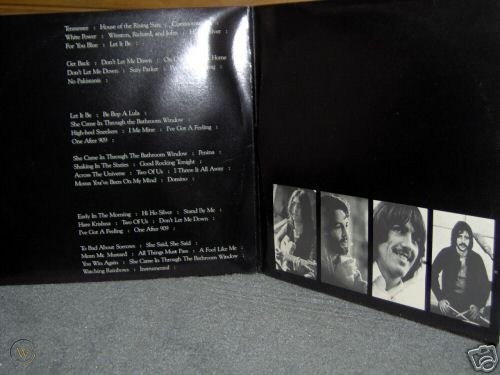

The so-called "Black Album," the second major

bootleg of "Get Back/Let it Be" rehearsals. Two LPs,

with package imitating the "white album," complete with embossed

"The Beatles" and folded poster inside. |

With this

pull-the-rug-out-from-under-you news, the “Get Back” matter receded in

importance, became almost moot. Right in the middle of a wave of new

Beatles album anticipation, there were. . .no more Beatles? Think:

waiting for a badly needed paycheck, rushing to the mailbox, and finding an

empty envelope.

Enter the walking

manifestation of musical irony, the Mefistofeles of this opera: Phil Spector.

On May 8, 1970, at long last, the mysterious, official

“Get Back” album, retitled “Let it Be” for no apparent reason, and produced

not by George Martin, but “re-produced for disc," whatever that meant, by

Mr. “Wall of Sound,” was released---cue final Sgt. Pepper chord. With

an embarrassingly plain black cover and the four almost blurry stills---the

only Beatles album to show the group as individuals---the LP would be

forever tainted with poignancy, disappointment, dismay, heartbreak over the

band’s ugly dissolution. Talk about spoiling the party.

This proved even more the

case for the “Let it Be” movie by Lindsay-Hogg, released only a few days

later. To put it charitably, his reduction of somewhere near sixty hours of

footage into an hour and 21 minutes was dreary, mostly conveying: acrimony,

hostility, lethargy, argument. The tone, if not intended angle, was one of

impending Beatles doom. Making matters worse, the film had been blown up

from 16mm to a grainy, unpleasant looking 35mm, so it came across---like the

“Get Back” bootlegs---as kind of half-assed. There on the big screen,

instead of the jovial “Magical Mystery Tour” Beatles (a better looking

film), or the down-to-earth “Hey Jude” Beatles, were. . .disinterested,

passive-aggressive Lennon, domineering, pretentious McCartney, disgusted,

simmering Harrison, and hangdog Ringo. “Let it Be,” the movie and album,

became the group’s de facto funeral, despite the (yawn) Academy Award for

“best score” that came the following year.

(And yes, I again

stumbled across the album at the House of Sight and Sound , not expecting to

find anything. This was the original, imported boxed set version, with a

huge book inside, documenting the sessions. I believe the asking price was

about five bucks---enormous, at the time. Once more, I rushed home to steal

money, but this time, when I returned, the album had been bought. I'm still

miffed! Today it goes on eBay anywhere from $500 to $1000, and up.)

To make things even

stranger, if this was possible, the expressed goal of the album being

live, with no overdubs, was tossed out by Spector, who infamously added

(very good) Richard Hewson orchestral scores and (very corny, saccharine)

ladies’ choirs to “The Long and Winding Road” and “Across the Universe”

(with lesser intrusion on “I Me Mine.”) I have this in common with

McCartney: I hated these productions at first listen. These were supposed to

be “chamber music Beatles,” without adornment. The mountain of musical

flowers heaped on “The Long And Winding Road,” it turned out, had even a

been a deciding factor in McCartney announcing his departure from the group.

He had lost control of his own work, after all. In sum, “Let it Be,” while a

respectable and interesting collection of songs, with several instant

classics, did not come within a zebra-striped crosswalk of the power and

invention of Abbey Road.

So here we were in early

1970, with a new Beatles album---but no Beatles---an album meddled with to

its detriment by a “stranger,” Phil Spector (who ridiculously omitted “Don’t

Let Me Down” because the single version had been on the awful, Christmas ’69

cash-in Hey Jude compilation album ordered by the odious new Apple

CEO, Allen Klein), plus a movie of the album sessions that produced the

opposite effect of what you expected Beatles movies to produce. I remember

walking out of the Fox Venice Theater in Venice, California, one late Sunday

afternoon, alone, head down, feeling like the world had ended. The fact that

The Beatles had been my main source of comfort during years of belittlement

and psychological tyranny by the archetypal evil stepmother, made the pain

all the more acute (a situation with which I expect many can identify, one

way or another.)

In short: “Let it Be”

became the most loused-up chapter in the group’s history. The cheese reeked.

Over the decades,

countless books and articles pondered how and why things could have gone

so wrong, and how on earth The Beatles had later managed to pull things

together with producer George Martin for “Abbey Road.” Lennon famously

dismissed the “Get Back” sessions as “the shittiest load of badly recorded

shit – and with a lousy feeling to it – ever,” and praised the job done by

Spector (whom he alone had delegated the task of turning the

tapes into an album.) Lennon even lauded the orchestra and voices on his

“Across the Universe,” never mind that the band’s contribution had been

mixed down to the point of inconsequential. Even I had a teency hand in

promoting the prevailing impression of disaster: one lengthy installment in

my massive 1983 eleven-part series about unreleased Beatles music in the

Los Angeles Herald Examiner---which fetched international headlines---was

devoted to the perplexing failure that was “Get Back.”

So that’s it, you say?

That’s the story? A bootleg “Get Back” LP capped off by the mixed bag

official 1970 Phil Spector-"reproduced" account, ironically touted on the

back cover, in strange PR-ese, as a “new-phase Beatles album?” The End?

Get back, JoJo, not even

close. “Get Back/Let it Be” went on to become simultaneously the most

unfinished and over-finished project in Beatles history---maybe recording

history. Consider:

The original bootlegs

presaged more (now legendary) bootlegs of the sessions, beginning with a

double-LP thing called “Sweet Apple Trax” from the Twickenham rehearsal

camera rolls (I picked mine up in 1972 in the back of the ur-Rhino Records,

Apollo Electronics, in Santa Monica), and later the so-called “Black Album,”

a two-disc LP designed like the "white album," in the mid-70’s. Both of

these, which featured run-throughs, rehearsals, fetch a fair number of dollars

on eBay today. This, in turn, loosed an avalanche of Beatles bootlegs

covering their entire career, from live recordings to acetates to BBC

recordings to studio outtakes. By the ‘80’s and ‘90’s, most of the “Get

Back” sessions were pirated in huge, ten-LP boxed sets selling for hundreds

of bucks. . .

And let us not forget the

original, actual “Get Back” album. Yes, there was such a Griffin. This beast

was birthed by quasi-producer Glyn Johns way back in 1969, and rejected (in

four different versions, exclamation point) by The Beatles, at the

time. (This probably had much to do with Johns’s terrible artistic decision

to go with less finished, more ragged song takes, to achieve a more

“authentic” feel. Gawd.) In 1985, I broke the exclusive news in the Los

Angeles Times of the appearance (once again, at swap meets, and bins of

used record stores, etc.) of a studio-quality bootleg of the first Johns

Get Back LP.

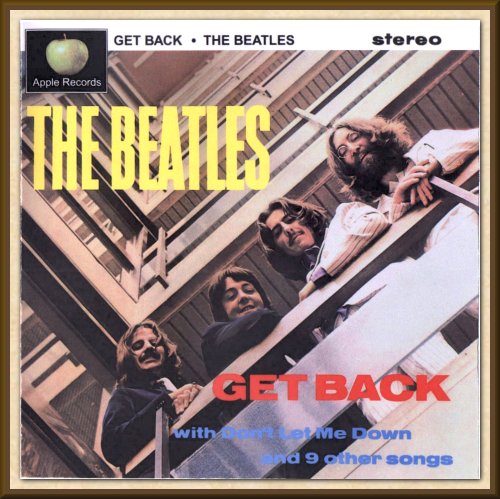

This album, as is now well

known, featured a cover photo of the 1969 Beatles in the EMI stairwell,

posed just as they had for their “Please Please Me” album in 1963. With

original Beatles press man Tony Barrow’s liner notes satirically updated by.

. .Tony Barrow---chiefly substituting song titles. A fabulous image it was,

making the “Let it Be” cover all the more wretched, cheap. The original

version read "Get Back, with Don't Let Me Down and 9 other songs." (A second

bootleg reproduced Johns' fourth pass at making an album, with the same

cover, but words changed to "With Let it Be and 11 other songs.") The article,

again, made international headlines.

Still with me?

"Get Back," the Johns version, bootleg # 1.

|

"Get Back," the Johns version, bootleg # 2. (Pass # 4.) |

In the 90’s, Apple

finally got into the bootleg spirit. There was an official Beatles

attempt to re-cast the “Get Back” sessions in 1995, with alternate versions

of “Get Back/Let it Be” songs on disc two of “The Beatles Anthology, Vol.

3.” This was a whopping fourteen songs, including a pretty spiffy studio

version of “Dig a Pony” not released elsewhere, plus now-legendary oldies

jams, mixed by redoubtable Beatles producer George Martin and engineer Geoff

Emerick. Right: the specter of Spector was nowhere to be found. Case closed?

Sure, and Trump has found

humility.

The bad taste left by

Spector’s bad taste on the “Let it Be” album not only dogged many fans, but

McCartney, as well, to the extent that---thirty-three years later, in

November, 2003---he sought to put the star-crossed project right, once and

for all, with an album clumsily titled “Let it Be. . .Naked.” Produced by

Paul Hicks, Guy Massey, Allan Rouse, McCartney’s pet project indeed yielded

a viable, indeed, rather wonderful “Get Back” album, as envisioned. No

orchestras, choruses---just the boys and Billy P. It had been renamed

“Naked” for marketing purposes only, in order to make it clear to buyers

that this was the "Let it Be" album denuded of Spector. Of course, it

wasn't---it was an entirely different album, with differen takes. To hear

the elegant, unreleased version of “The Long and Winding Road,” complete

with a little organ solo by the great Preston, was worth the price of

admission alone. This album, thank you Paul, went a long way toward finally

repairing the “Get Back/Let it Be," becoming an indispensable part of the

Beatles canon. I consider it the definitive album of the project. And get

this: the original “Let it Be” movie---last seen released to video in

1981---was, with a bonus DVD, to have accompanied “Let it Be. . .Naked,"

but. . .

Bang, bang, Maxwell's

silver hammer came down upon its head.

The problems with the 1970 Lindsay-Hogg film turned out to

still be problematic in 2002. As Neil Aspinall, Apple Corps Director, and

Beatles right-hand-man since the beginning, said in an interview:

"The film was so

controversial when it first came out. When we got halfway through restoring

it, we looked at the outtakes and realized: this stuff is still

controversial. It raised a lot of old issues."

And so it went back into

limbo.

Over the years since that

aborted attempt to re-release Lindsay-Hogg's “Let it Be,” Ringo went on

record repeatedly as saying that he hated the film, found it “joyless,” and

remembered the sessions as upbeat, even fun. (“I’ve

always said how much joy there was during those sessions that wasn't in it

before now,” he said after the release of “The Beatles: Get Back.”)

There

were even calls from journalists for the original, grainy version to be

junked entirely, and a new movie cut from the existing footage. (Again, I

had a very small voice in this, with a lengthy commentary calling for an

entirely new “Get Back” movie in the venerable Beatles fan publication

edited by Bill King, Beatlefan.)

And in the end.

. .that’s what happened---but not without an episode worthy of a

Sherlock Holmes mystery. Yes, folks, it’s time for The World’s Funniest

Beatles Criminals! Turns out that most of the footage of the sessions

had disappeared from a cupboard or two during the dissolution of the

original Apple Records, when many things were disappearing from many Apple

cupboards. In this case, thanks entirely to Interpol, it was discovered that

ex-Apple employee Nigel Oliver had either pilfered or received 55 hours

of film of the greatest group in music history. Just a little nick,

that’s all. Oh, and heavens to Krishna, Nigel also seem to have acquired

George Harrison’s 1960’s passport. (Yeah, that’s me, officer---I used to

be in the Beatles!) How and why he imagined this would not be noticed,

or traced to him, is perhaps best not contemplated. Anyhow, Oliver pocketed

£25,000 after selling the camera rolls to a couple of Dutch, uh, “traders.”

In 2003, Interpol raided a Netherlands warehouse, and, as Peter Jackson

tells it:

"They did a sting

operation in Amsterdam – and recovered all of the tapes, apart from 40.

There were about 560 quarter-inch tapes.We managed to find some of that

sound through other sources."

The words, “apart from

40,” should send eyebrows to scalplines. Where are these 40, one wonders,

and is Interpol still on the case? Unknown. In any event, Jackson’s

challenge was suddenly feasible: match the (long bootlegged) sound of the

sessions to the newfound images.

"They used only two 16mm

cameras... no clapperboard,” Jackson explained in interviews. “And the audio

was out of sync. I had to match everything. . .I

had 60 hours of footage and 130 hours of audio. It was a big job that has

taken me four years.”

And so this unlikely,

serepentine chronicle also became a story of film restoration.

As

for Oliver, who

nearly deprived the world, and the Beatles’ legacy, of what has

certainly become the most important visual document of John, Paul, George,

and Ringo, he was diagnosed with schizophrenia, and given a two-year

“supervision order” (read: be a nice boy, and check in with

authorities regularly) for “handling stolen goods.” An accomplice, one Colin

Dillon of Berkshire, England, was given a suspended sentence of four months.

No Rose and Valerie screamed from any galleries.

Talk about The Long

and Winding Mr. Toad’s Wild Ride."

But,

as they say in what

passes for TV news, wait, there’s more!

After being bootlegged

for decades, the original, deliberately rough-around-the-edges

Johns-produced “Get Back” LP---his first version---was finally officially

released by Apple(!) as part of the November, 2021 “Let it Be” boxed set

remixed, remastered by Giles Martin and Sam Okell. If you’re keeping score

at home, that would be five different albums (six if you included the 2009

remaster) from the four-week 1969 sessions produced by seven different

producers.

Gasp.

So where does all this

leave things? Done? “Let it Be” is at last “Let it Been?” Is this the end of the cheese that the mouse nibbled way back in 1969?

Uh, well, maybe not.

There are still those 40 missing reels of film. . .

BACK TO PAGE ONE |

![]() Get

Back/Let it Be

Get

Back/Let it Be