|

MIXED FEELINGS ABOUT

'WHITE ALBUM' REMIX

Glistening clarity aside, project marked by poor choices,

expedience, lack of imagination

By Rip Rense

(copyright Rip Rense, The Rip Post 2019)

Giles Martin deserves

accolades and thanks for his handling of the re-release of The

Beatles’ so-called “white album," officially titled The Beatles. At

least I think he does. Doesn’t he? Well, yes, he does, but. . .

It’s puzzling, the limited imagination brought to re-issuing this ungainly

batch of songs (plus one superb avant-garde pastiche), and dozens of

outtakes. There is a distinct down-side to Giles Martin’s superb remix. A

down-side to “superb?” Did I just write that?

Here’s the thing: Martin said in many interviews that he approached the

remix with essentially one idea: to have the group vocals more or less front

and center, and the instruments spread out behind and around them. With some

variations on this formula, that’s what the new “white album” seems to be,

and it is, undeniably, a thrill to hear.

In

other words, legendary Beatles producer George Martin's son employed one

basic plan (with some tweaking) for a panoply of songs that famously embody

extremes of instrumentation and personality---from Lennon with solo guitar

(“Julia”) to McCartney with small orchestra (“Martha My Dear”) to Beatles

playing raucously in a small room (“Yer Blues”) to odd arrangements with

only three Beatles (“Long Long Long.”)

In the main, it worked. The new mix has such immediacy, such presence, such

detail, such clarity that one glosses over inherent troubles in the album.

Troubles? Given the ecstatic reviews of the Giles revision, it seems almost

sacrilegious to suggest built-in deficiency. Yet the “white album” is a

wildly uneven mix of styles, songwriting, indulgences---from polished gems

(“Revolution 1”) to crude throwaways (“Why Don’t We Do It In the Road?”) to

oddball trifles (“Everybody’s Got Something To Hide Except For Me and My

Monkey”) to unlikely, smashing successes (“While My Guitar Gently Weeps.”)

It is nothing if not indulgent.

Raving critics have utterly forgotten this. Almost to a person, they

minimized: the dramatically inconsistent aspects of the original album, the

factionalized recording sessions, the rancorous band conflicts, Lennon’s

destabilizing use of heroin, Harrison’s disgruntlement, Yoko Ono’s sudden

and irking presence, George Martin simply bailing out for a while (leaving

21-year-old Chris Thomas to produce), Ringo quitting (!), and other factors

that led McCartney to refer to the whole thing, kindly, as “the tension

album.”

Not to bore with faux “scholarship,” but it should be

summarized here that The Beatles returned piecemeal from India with a glut

of 30 new songs and, for many reasons (lack of Brian Epstein’s guidance,

Lennon’s sudden divorce, running their idealistic, madcap new company,

Apple), an equal surplus of confusion and frustration. Geoff Emerick’s

description of Lennon’s bizarre (drug-stoked) behavior and barely controlled

rage at the early sessions---which led the invaluable, patient engineer (de

facto co-producer) to quit (!)---is just plain scary. The Beatles simply

couldn’t stand one another, Emerick says---call it burnout, for

convenience---and this is borne out by their having worked largely

separately during these sessions, as is well known. (Emerick told me he was

never able to comfortably listen to the album, for these reasons.)

Yet Giles Martin has put a new spin on the matter, which, of course, is good

public relations. Listening to the sessions, he says he was impressed with

how assiduously the group worked, how little friction there was, how they

seemed to be having a fab time. All of this is, of course, easily

explained by Ringo’s famous remark about how, once the red light was on and

the band was concentrating on music, all acrimony fell away. Or most.

Not on tape, apparently, are Lennon and McCartney nearly coming to

blows over “Obla-di, Obla-da,” and, more incredibly, McCartney shouting

profanities at George Martin (over the same song), and other terrible scenes

revealed in Emerick’s fine memoir, “Here, There, and Everywhere.” And yes,

there was the famous temporary resignation of the redoubtable Ringo, leaving

McCartney to carry on as drummer on “Back in the U.S.S.R.” and “Dear

Prudence," and Harrison bringing Eric Clapton to the sessions as an antidote

to acrimony. Incidental friction? A fab time? I think not! The

(interminable) recording of the “white album” was nothing less than a

crucible for all concerned.

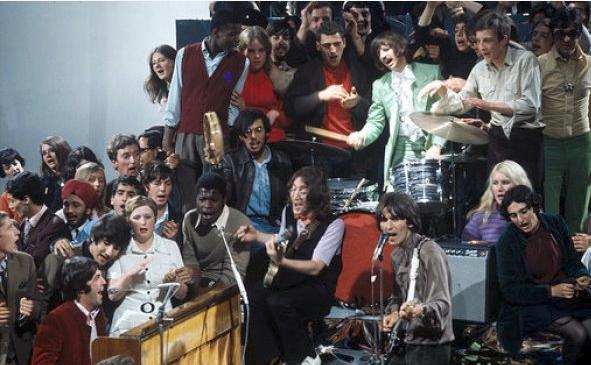

George Martin and The Beatles during the "white album" sessions

in a photo that does not even faintly suggest the turmoil of the

project. |

Giles Martin, who insists that the legendarily difficult "white

album" sessions were, in the main, constructive and trouble-free.

A Lennon sketch of the band during the "white album," its

togetherness belied by rage, a near-fist fight, the resignation of

Ringo, engineer Geoff Emerick, and temporary bailing out by

producer George Martin. |

But this is how stupendous the new mix is---it imbues the two records with a

sort of continuity that they have never had before, smoothing out jagged

edges and inconsistencies. What has always felt like a grab-bag of jarringly

different work has acquired some cohesion, courtesy of Martin’s broad-stroke

remix approach. Whether he intended this result or not, it was a great move.

The changes in “Dear Prudence” and “Long Long Long” are particularly

revelatory. “Prudence” has always sounded cobbled together, to these ears,

with the bass and drums clumsily laid over the top. The new version? A

graceful, organic group performance (even lacking Ringo.) And “Long Long

Long” no longer sounds peculiar, unwieldy---more like an inspired, planned

arrangement. Amazing.

The net effect: the “white album” no longer feels like a

record made in the studio. It sounds like The Beatles playing all the songs

on stage, live, twenty feet in front of you. Taken as such, it is

breathtaking. Whoever imagined such a thing possible? The band, even on

crummy sound systems, seems to breathe and play right in the room. The

improved presence is akin to a myopic donning glasses for the first time.

This is a gift, a treasure, a minor miracle. After all, underlying The

Beatles’ continuing---and yes, still growing---myth and popularity, is a

desire to have them back, alive.

Yet something is lost in the process, isn’t it? What is that something?

Obvious to say, it is nothing less than Giles’s father’s mixes---mixes that

created individual character for each song, emphasizing some aspects,

de-emphasizing others. Mixes that included giving particular instruments

deliberate presence, which brings us immediately to McCartney’s bass. (Note:

Lennon and McCartney were also present for a 24-hour marathon devoted to

mixing and sequencing the “white album”---The Beatles’ longest session.)

It is no revelation that Paul’s melodic virtuosity on the instrument is a

huge part of the Beatles’ sound and success. At best, his basslines stand as

counter-melodies, compositions that become indispensable parts of a

given song’s arrangement. (Same is true of Ringo’s drumming.) Nowhere is

this more apparent than on “Sgt. Pepper,” where Paul literally stayed in the

studio until dawn, night after night, working out bass parts for many of the

album’s otherwise finished tracks.

I’m not sure Giles Martin understands this, or if he does, it seems he gave

this factor less priority in his “white album.” The very sound of Paul’s

bass on the new “white album” is largely the same generic, low bass-y

rumble, song after song. This is simply not the case on most Beatles albums,

beginning with “Revolver.” The bass was always given special character, and

often a distinctly un-rumbling---far more lyrical---voice, largely courtesy

of Emerick. (See: “With A Little Help From My Friends.”)

In putting the instruments in the Giles “live band” context,

the “arrangement” importance of the bass, to cite one aspect, has been

reduced, even sacrificed. How? I cite “Revolution 1." Listen to the original

release, stereo or mono, and note how Paul’s walking bassline, especially on

the “you know it’s gonna be” sections is vital to powering the song

along, giving it tension, lift, elan. To my mind, the work is

unthinkable without it. Yet It is buried in the Giles Martin version,

relegated to deep background, its impact almost subliminal. This happens too

often for my taste in the new album mix. Reduced and sometimes absent is the

craftsmanship of George Martin’s original placement of voices and

instruments. I’m sure Giles would agree with this, incidentally, as it was

not his intention to replace his father’s work, but rather simply to hear

The Beatles in a different context.

I could cite similar examples, but I’m going to leave off after

one more: Ringo’s drums on “I’m So Tired.” Starr has raved in interviews

about how much he loves the new drum sound on the Giles mix. That’s fine,

but that is not to say that the new drum mix is always superior to Martin

pater familias’s. Just isolate the two little drum solos in this song.

Compare. Use any sound system. The original mix has those solos viscerally

pumped (Ringo always played loud, by the way), while the new mix leaves them

sounding flimsy, weak-kneed, relegated to background. It is a stunning

difference, and not for the better.

So when you find yourself aping critics’ praise for the new mix, remember

these two examples, and do a full album comparison of original and revision.

While much is commendable and grand about the 2018 revision, I submit that

George Martin’s is the more artful, nuanced, complex. Which stands to

reason, given that he was treating the songs like individual works of art,

as opposed to live performances.

In a nutshell: the original mix plays like a record, the new one plays like

a concert.

Which brings me to the lack of imagination I mentioned at the outset. Here I

refer to Giles Martin’s fundamental approach to the overall release. For all

the bounty of outtakes and acoustic demos (both obvious “musts” for this

projects) there were strange misfires and missed opportunities, in my view.

One very obvious misfire, or at least a jarring peculiarity: Martin chose to

include outtakes of "Across the Universe," "Lady Madonna," and "The Inner

Light," when these songs are not even part of the "white album"

sessions (they were recorded in February, '68," while the "white album" did

not commence until May 30.) While he did properly include outtakes of

"Revolution" and "Hey Jude," recorded in the middle of the "white album"

sessions, he---quite incredibly---did not bother to remix the finished

versions. Why?

Recording Lennon's "Good Night," with Ringo doing the lead

vocal. Lights purposely dimmed for atmosphere.

The Beatles-only version is the highlight of the outtakes in the

new "white album" remix. |

Yes, of course the “Escher demos” of all the acoustic rehearsals (including

never-released songs such as “Child of Nature”) were requisite for a full

“white album” edition, and well done to Martin for finding a pristine copy

of the tape at the Harrison Estate, and upgrading the quality. Very

disappointing, though, is the fact that the three CDs of outtakes

were released unmixed. Exclamation point. Martin justified keeping

“things as dirty as possible," as he put it, by saying he wanted fans to

hear the outtakes exactly the way he did the first time, to have that same

thrill of discovery.

Uh. . .that’s a pleasant notion, but one wonders if it was done out

of expediency, given the time necessary to invest in the realizing the

enormous “white album” reissue. Deadline pressure, in other words. Releasing

unmixed Beatles music is almost unprecedented (the exception being the

peculiar Internet-only release of some early sessions in order to protect

copyright); all the outtakes on the three double-CD Anthology

releases were carefully mixed by George Martin.

So the “white album” outtakes exist in warts-and-all condition, instead of

being polished---which is what you would expect of a bootleg, not an

official album. One especially frustrating example is the version of “I’m So

Tired” with Harrison guitar echoes. A bootleg of this take has been around

for years, prompting debate as to whether the guitar echoes were “outfakes”

or actually Harrison. To this ear, the (yes, Harrison) guitar adds much to

the song, as do a very tantalizing bit of three-part harmony vocals heard

only at the outset on the Giles-selected outtake. What? Guitar echoes?

Harmony vocals? Really? Yes, it turns out that this was a band effort---not

merely a Lennon song dashed off with McCartney and Harrison barely in

evidence. The Harrison guitar lines are buried in the unmixed version; the

harmony vocals blare, wildly out of balance. What on earth would have

been the harm of properly mixing it, repeating the harmony vocals

at appropriate points in the song, mixing up Harrison’s guitar parts, making

it effectively a viable alternate version with more of a band feel? Remember

that George Martin sometimes actually created new alternate versions of

songs on Anthology (“Strawberry Fields Forever,” for instance), so

why not here? This is one of many missed opportunities.

Then there is the choice of the outtakes. Giles Martin said he relied

on “two Beatles experts” to make the initial choices (did he mean Ringo and

Paul?), which he either approved or vetoed. Well, for starters, why did the

“experts” suggest so many instrumental versions? Is it really of interest to

hear the backing track to “Piggies?” (the non-“white album” track) “Lady

Madonna?”, “Martha My Dear?” Did they run out of outtakes, or, more likely,

time to make better decisions, and instead padded things with instrumentals?

(To be fair, the instrumental version of “Everybody’s Got Something to Hide

Except for Me and My Monkey” was worthwhile.) I would much rather hear an

alternate run-through of the group playing just about any song on the album,

than a mildly different version of, yawn, “Rocky Raccoon,” or

“Blackbird.” Consider this: McCartney was singing the “Not when he looked so

fierce,” etc. lines of “The Continuing Story of Bungalow Bill” before Lennon

rather insanely gave them to Yoko Ono. Isn’t there an outtake with Paul

doing them? If so, why was this not included? Mark Lewisohn has quoted the

several charming, hilarious spoken word intros that Ringo did for the

(wonderful) version of “Good Night” that features all four Beatles. Why is

only one such intro included here? And why wasn’t the full-Beatle

version given a little fine-tuning where needed?

The most egregious decision in the new “white album” package, however, was

to not restore “Revolution 1” at its full length. This is just unforgivable.

The 11:32 performance---take 20---featured extra Harrison/McCartney vocal

parts ("Mama, Dada. . ."), and all manner of effects intended to fulfill

Lennon’s design of the song devolving into sounds of “revolution.” It’s a

great take, lacking only Lennon’s stinging guitar overdub and George

Martin’s artfully couched horn arrangement. Instead, Giles Martin bafflingly

chose take 18, which lacks most of those effects(!), vocal parts, and

features Lennon endlessly and painfully screaming “all right” forever. And

ever. And ever. Gad. Restoring take 20---and mixing in Lennon’s lead guitar,

George Martin’s horn arrangement---and adding parts earmarked for the final

version, but never added after Lennon decided to do the “chaos” section

separately as the avant-garde pastiche, “Revolution #9”---would have yielded

a glorious new version of the work, living up to Lennon’s original

vision, not the weird, incompletely orchestrated (and tiresome!) curiosity

that Giles chose. It’s a shameful, sloppy mistake in judgement, nothing

less.

The legendary quasi-live performance of "Hey Jude," done

during the "white album" sessions.

A high point of good feeling in 1968 for the band, and possibly the world.

|

This is what I meant by “imagination.” Why not release the outtakes

in best possible sound? It’s ludicrous not to have done so. Why not restore

the original version of “Revolution 1," really the lost treasure of the

whole album? Such a missed chance is just tragic---especially in a release

that touts outtakes and alternate versions. I’ll bet dollars to

donuts that George Martin and Geoff Emerick would have restored the long

version of “Revolution 1” for this project. And speaking of George Martin,

and imagination, here’s another opportunity that Giles and Apple missed, and

one that would have yielded a great deal of additional revenue, if that was

a priority. Whimsical? Yes. Gratuitous? Some might think so. But. . .

George Martin tried in vain to convince The Beatles to release the album as

a single disc, using the strongest efforts. There have been many articles

for many years by persons claiming expertise as to what such an album might

have included. In short, there has been a long-standing parlor discussion

about the matter, of interest to countless fans. Why not fulfill the

original producer’s wish? Why not release a “single disc” version of the

album, a “what might have been” enterprise, in the overall package---or even

separately? With some different versions, perhaps? Give it a new name, even.

A ripoff, you say? Just cashing in on the same songs, in a different running

order? Not necessarily.

Are there any notes left behind---on paper or tape---by the senior

Martin as to what his preferences might have been? Are there a few

viable alternate versions that could be used instead of the released

versions? Answer: yes. The Beatles group version of “Good Night,” many have

written in recent months, might have just as well closed the original album

as the (deliberately schmaltzy, at Lennon’s request) version with orchestra.

Add to this a restored version of the long version of “Revolution 1”---and

possibly other items including the Ravel-esque instrumental prelude George

Martin wrote for “Don’t Pass Me By,” and the extended “Yer Blues” with the

full Harrison guitar solo(!) on the outtake, or even the original (yet

unreleased!) version of “Across the Universe” (Giles included take 6 on the

“white album” package) and you have an intriguing, powerful gambit on your

hands! Both in terms of art, and, yes, forgive me for pointing this out. .

.marketing. One possible version of a single disc:

Side one: Glass Onion/ Obla-di, Obla-da/ Bungalow Bill/

While My Guitar Gently Weeps/ Blackbird/ (George Martin orchestral intro)

Don’t Pass Me By/ Happiness is a Warm Gun. Side two: Back in the USSR/

Piggies/ Across the Universe (unreleased original version at correct speed)/

Hey Jude/ Julia/ Revolution (Take 20, completed, at 11:32)/ Good Night (Band

version.) If you are of the opinion that “Hey Jude” should be excluded

because it was a single, then substitute “Mother Nature’s Son” or “Honey

Pie.” Don’t like “Bungalow Bill?” Substitute “Sexy Sadie” or “Dear

Prudence.” Call the album “Revolution,” and commission a new cover, subject

to approval by all concerned parties.

Why. The. Hell. Not.

This not only would be a creative, fun enterprise---and a great tribute to

George Martin---but it would have furnished the hard evidence of how potent

the album might have been, had the group gone with only stronger material on

one disc. It would be nothing less than an addition to The Beatles’ legacy

and catalogue of the first order, especially with several alternate

versions.

There is a point where the “don’t tamper with history” cliché just

becomes silly, and that point is where history can be added to

meaningfully. This could have been done with the “white album” reissue, and

to great effect, with: fully mixed outtakes, more thoughtful choices of

outtake material, a restoration of the long version of “Revolution 1,”

restoring outtakes into, effectively, alternate versions (comparable to

things George Martin did on “Anthology”), and even a what-if single

disc version of the project.

All of which are glorious opportunities that Giles Martin,

his mysterious “Beatles experts,” and Apple, for all their laudable work,

missed.

|

![]() Riposte Archive

Riposte Archive