RIPOSTE

by RIP RENSE

|

|

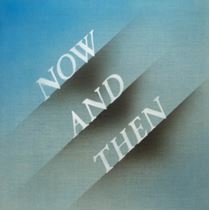

The Beatles' "Now and Then:"

time warp, or timely?

(Nov. 10, 2023)

It’s like walking

into the arena long after the concert ended, and seeing a

last few bits of confetti suddenly shake loose from the rafters.

Or perhaps, it’s more like visiting that arena fifty years after the

concert, and finding some old confetti in a corner, behind some boxes.

Then throwing it into the air.

I mean, whoever thought there would be a new Beatles song in 2023?

It’s like saying there is a new 1965 Mustang, a new Sean Connery James

Bond movie, a new outfit modeled by Twiggy, a new episode of “Batman”

with Adam West. In terms of surreal, this is up there with “I Am The

Walrus.”

Next thing you know, Ringo Starr will still be on the road with a band

at age 83, Paul McCartney will tour Australia at 80, and there will be a

new Rolling Stones album.

Oh,

wait. . .

A new

single! |

Sirs Ringo and Paul in 2023 |

Once upon a time, the world, or so it seemed, waited for new

Beatles songs the way dogs wait for walkies and kids wait for Christmas.

What would the next single sound like? How could they top “Lady Madonna”

or “All You Need is Love?” What? Paul is playing piano? What’s

happened to John’s voice? What’s with George and the India stuff? Ringo

is singing “Good Night?” I thought it was Paul!

There was absolutely no predicting the style or substance of Beatles

music---especially after 1965, when both started to drastically change.

Songs now long blithely accepted as mega-classics, such as “Day Tripper”

and “Yellow Submarine,” were shockers. Every single new tune was a

stylistic and creative revelation; like a new species of Beatles. The

anticipation and excitement? No more intense than sun spots. The mood,

the joy, the interest, the surprise . .it’s simply impossible to convey

to anyone from today’s culture, where (mostly commercially

contrived/demographically calculated) music “streams” like raging

for-profit rivers.

But it was more than just the explosive invention of The Beatles that

was at issue, as countless writers have noted over the decades. . .

In the ‘60’s, the world was in genuine fear of nuclear war.

Genuine fear. Soviet Union Premier Nikita Krushchev was on TV all the

time, interrupting after-school cartoons in a propaganda commercial,

yelling “We will bury you!” at the USA. Terrifying! Young men had to

worry about being yanked out of college and sent to die or be maimed in

Vietnam. Assassinations in the U.S. and abroad came to be frequent

news. News itself was just one TV half-hour a day (per each of three

networks), with local fare still in infancy; mighty newspapers still

defined information and discourse. Telephones? They were were plugged

into walls and dialed, took no pictures and had no “apps,” while mostly

black-and-white TV sets boasted seven stations (or less). “The Beverly

Hillbillies” and “Bewitched” were long-running hits. Seat belts in

cars were a new requirement, FM radio was still “experimental,"

and most people were (gasp) courteous (!). The country seemed to be

disassembling under anti-Vietnam protests, the civil rights

movement, the beat/Bohemian eco-ethos of hippies, the murder of Kennedys

and Martin Luther King, the fear and loathing

of Nixonian Republicans. There were three billion people in the world,

for God’s sake---not eight billion, as there are today (220 million in

the USA, as opposed to 330 million today.) Lines were short! You could

move around. You could breathe.

It is cliché to say that The Beatles became an unwitting antidote to all

the chaos, death, fear; a from-outta-nowhere medicine for

melancholy after the paralyzing assassination of President John F.

Kennedy. Country Having Nervous Breakdown, meet John, Paul, George,

and Ringo. Just hearing yeah yeah yeah after the oh, no

of November 22, 1963 was a very big deal---let alone you know it’s

gonna be all right during the tectonic tumult of 1968, what with the

killings of Martin Luther King, Robert F. Kennedy, and the riot that was

the Democratic convention. In just

eight years, the quartet seemed to evolve from exuberant, effervescent,

fluffy, Marx-Brothers-ian boys into hirsute philosophers resembling

nothing if not Aristotle, Leonardo, Swamis, even Christ. I mean, really

folks, you had to be there.

In short, in the ‘60s, a new Beatles song was an event.

And so it is again.

But is "Now and Then" a Beatles song, really? The old McCartney line about

why it would be difficult for The Beatles to reunite---“you can’t reheat

a souffle”---doesn’t apply, because some of the souffle ingredients

don’t even exist anymore. How, after all, do you make a Beatles song

with John Lennon, George Harrison, producer/arranger George Martin gone?

Let alone McCartney’s voice sounding a bit creaky? Here’s how:

You take the fourth Lennon homemade cassette recording given to “The Threetles” by Yoko Ono, “Now and Then,” in 1994. Yes, the

song that the

three worked on for just one day in 1995, adding try-out guitars and

vocals and drums. The one they discarded because the original tape had a

loud buzz on it, an echoey piano, and the sound of a TV set (some say)

in the background. You settle for doing just two Lennon-written reunion

songs, “Free as a Bird” and “Real Love,” and have done with “Now and

Then.” Until, that is, director Peter Jackson’s crew developed an

artificial intelligence program winkingly dubbed MAL 9000, in tribute to

The Beatles’ redoubtable assistant, Mal Evans (after “Hal 9000” in

“2001: A Space Odyssey) in order to separate Beatles voices from other

sounds while making the brilliant 2021 documentary, “Get Back.” And you

use this breakthrough program to separate Lennon’s voice from everything

else on that buzzy, cluttered mono 1977 home tape, then clean the

vocal up and give it studio quality fidelity. A miracle, really.

This is what happened. And lo and behold, the dormant old Beatles

engine somehow sputtered to life, even with a couple cylinders missing

and a clogged carburetor, for one last spin around the block.

Jump-started entirely by McCartney, who---as the “Get Back” doc

demonstrated---probably loved the group most of all. George’s acoustic

and electric guitars of the 1995 session were intact, and duly added to

the Lennon vocal. McCartney overdubbed a characteristically lyrical bass part, a piano, the "Because" harpsichord, and a Harrison-tribute slide guitar solo(!). Of course,

he called up the only other available Beatle in this world, Sir Ringo

Starr, for drumming duty---and to record background vocals

together.

Still, this gentle song of loss and longing really begged for the

cake-icing that was a George

Martin string arrangement. Voila! McCartney collaborated in writing one

with Martin’s producer son, Giles, and one Ben Foster. At last, in a

touch of characteristic Beatles whimsy, background vocals were

brilliantly mixed into the proceedings, taken from “Eleanor Rigby,”

“Here, There, and Everywhere,” and “Because.”

The result:

“It was incredibly touching to hear them working together,” said Sean

Ono Lennon, “after all the years that Dad had been gone. It’s the last

song my dad, Paul, George and Ringo got to make together. It’s like a

time capsule and all feels very meant to be.”

As for Harrison, who cancelled the original "Now and Then" sessions (and

who also rejected the Lennon reunion song, "Grow Old With Me," later recorded

by Ringo), Olivia Harrison said he would have

“wholeheartedly” joined the proceedings because of the MAL 9000

technology. And speaking of heart:

“It was the closest we’ll ever come to having him (John)

back in the room,” said Starr. “So it was very emotional for all of us.

It was like John was there, you know. It’s far out.”

For the inevitable critics who will dismiss “Now and Then” because it is

cobbled together from many sources and times and places, and that the

group did not record it together, well, such was the case with many of

the songs on the “white album" and "Abbey Road." Hardly disqualifying.

Is it above criticism? No. The song would have been stronger had

McCartney not excised Lennon’s original "I don't want to lose you"

bridge simply because it contained one line of scat-singing (which

actually sounded nice, or could have been replaced with a solo guitar

lick.) And Paulie really shouldn’t have imitated Harrison’s slide

guitar, when an actual Harrison solo could have been fashioned from

George’s solo work, beginning with his Grammy-winning double-lead guitar

instrumental, “Marwa Blues.” But as Lennon sang in “Dig a Pony,” you

can imitate everyone you know. . .

In the end, is “Now and Then” another brilliant, innovative

“Strawberry Fields Forever?” Or something simpler, in the vein of

“Julia” or “In My Life?” Certainly more the latter, as this is a fairly

straightforward, plaintive ballad from a period where a reflective,

semi-retired Lennon regularly

dabbled with song ideas at home in the Dakota. The song was probably

unfinished (Lennon’s songs often, if not usually, underwent many

iterations before the final take), and seems more like two or three song

ideas linked together. Yet they fit. And the chord changes are more of

the subtle minor key ilk that Lennon was developing toward the end of

his short life.

What is it about? This, of course, is up to the listener. McCartney has

noted that one of the last things, if not the very last thing, that

Lennon said to him during a phone conversation was, “Think of me every

now and then, my old friend.” So there is that private association for

him. For Yoko Ono, though, there was a very specific importance to the

song. She told me exclusively in 1995 that she gave “Now and Then” (she

referred to it as “I Don’t Want to Lose You”) to the other three for

“therapeutic reasons.”

“I thought this was a song which would release

people from their sorrow of losing John,” she told me. “By listening to

the song, they will eventually be able to release their sorrow, and

arrive at an understanding that, actually, John is not lost to them.

People who loved John are growing with John---by carrying their memory

of John in their hearts. Paul, George and Ringo lost a great friend as

well. If they sung this song from their hearts it would have helped many

people around the world who felt the same.”

This last Beatles song, as McCartney has declared it to be, is

entering a world almost as different from the ‘60’s as the 19th

century differed from the 20th. Technology, led by computers

and Internet, has destroyed and/or rearranged every bulwark aspect of

the culture alive in the sixties, in terms of social and economic

structure, and it has radically changed human behavior and sensibility.

Narcissistic preening and banality define much so-called popular

music; mayhem and ugliness infest movies and television; public

discourse has become crude, reactionary. Something as elegant as a new Beatles song today

seems not quite as out of place, alien, as a new

novel by Steinbeck, a new poem by Dickinson, a new symphony by Brahms.

And yet. . .assassinations then, assassinations now. Bellicose

Russian leaders then, bellicose Russian leaders now. Chaos in our

country then, chaos in our country now. Nuclear war threat then, nuclear

war threat now. Is The Beatles' "Now and Then" really so out of place

today?

The "Threetles" circa 1995, during the reunion

sessions. |

"NOW AND

THEN" WITH ORIGINAL BRIDGE

MORE ABOUT "NOW AND THEN"

RENSE'S ORIGINAL 2005 COVERAGE OF "NOW AND

THEN" IN WASHINGTON

POST

Copyright 2023 Rip Rense, all rights reserved

![]()