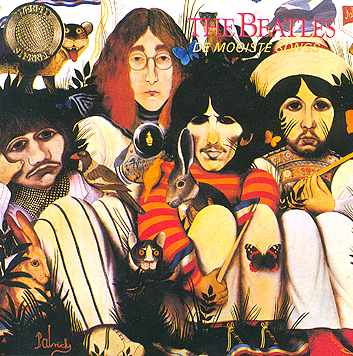

Illustration designed in 1968 by Alan Aldridge for "The

Beatles' Illustrated Lyrics."

SAY YOU

WANT A (new) REVOLUTION?

by Rip

Rense

(March 3, 2009)

copyright 2009 Rip Rense, all rights

reserved

The

recently leaked ten-minute-plus version of The

Beatles’ “Revolution 1,” with various vocals and avant-garde

effects added by the group and Yoko Ono, is not only the

most important Beatles musical revelation since “Anthology”

in the mid-‘90’s, but hard proof that there is more fabulous

material to be mined from original session tapes.

The track, possibly a

copy of a rough mix that Lennon took home after the June 4,

1968 session, sounds just as renowned Beatles authority Mark

Lewisohn described it in “The Beatles Recording Sessions:”

10:17 long, with additional George/Paul vocals of “Mama. .

.Dada” repeating many times during the fade-out. This was

take 18, the same as was edited down for the “white album,”

marked by what Lewisohn calls “pure chaos” in the last six

minutes, with:

“. . .discordant instrumental jamming, plenty of

feedback, John Lennon repeatedly screaming ‘all right,’ and

then, simply, repeatedly screaming, with lots of

on-microphone moaning by John and his new girlfriend, Yoko

Ono, with Yoko talking and saying such off-the-wall phrases

as ‘you become naked’ and with the overlay of miscellaneous,

home-made sound effects tapes.”

It

is, Lewisohn says, “riveting,” and no further accolade

is necessary. The track is a lost gem. (Even in the

profoundly unlikely event that this version has been

miraculously simulated with tape looping and fake vocals, it

still would remain a winning demonstration of the worth of

releasing the long version of the song.)

Not only is “Revolution

1-A,"

as some are labeling it, first-rate listening, but it is a

missing puzzle piece in a picture of an increasing creative

schism between Lennon and McCartney, and factionalizing of

the band. The first song undertaken for the “white album,”

“Revolution 1” (called “Revolution” until the single version

was recorded) precipitated tension, disappointment on

Lennon’s part, even a minor showdown between John and Paul

(described by former engineer Geoff Emerick in his book,

“Here, There, and Everywhere.”) It has, in short, an amazing history.

First, the ten-minute

session of May 30, 1968, was, not surprisingly, rejected for

consideration a single, due to length. As if that wasn’t

enough, the (fabulous!)

4:12

edited mix was also later nixed as a single by Paul and George

for not being “upbeat” enough (gasp---it would have been a

hit.) This led Lennon to (angrily?) remake “Revolution”

a month later, as a shockingly gritty rocker for half of

what is probably the most famous single in music history:

“Hey Jude/Revolution” (minus the winking “shoo-be-doo-wop”

vocals of Paul and George.) Even lack of chemistry and

cooperation yielded creativity in this remarkable band.

There is also substantial Beatles history wrapped up in

the so-called “1-A.” Much to the puzzlement of Paul, George,

Martin and others present, the recording marked the first

time that Ono joined a Beatles session, a habit she

maintained until the group broke up. What’s more, “1-A”

certainly marked the emergence of her heavy influence on

Lennon---in terms of social activism in the startlingly

direct, political lyrics, and the nifty avant-garde pastiche

over the song’s last six minutes.

Further, it exposed and

defined a growing creative rift between Lennon and McCartney

that led them to record very much apart during the “white

album” sessions. Lennon wanted no more of Paul’s bouncy

melodies and music-hall influenced ditties (which he

referred to derisively as “granny songs”), instead pushing

to move the group in a more hard-edged, experimental

direction---to be evidenced by such “white album” works to

come as “Yer Blues,” “Happiness is a Warm Gun,” and most

spectacularly, “Revolution # 9.” (And McCartney acceding

with “Helter Skelter.”)

The titanic “Rev.

# 9,” easily the most controversial of all Beatles

compositions, grew entirely out of “1-A.” Lennon, hooked on

the sheer fun of creating sound sculpture from eclectic

noises, spoken quotes, musical bits played backwards, etc.,

set about expanding the work done during the last six

minutes of “1-A” until it became its own highly ambitious,

ever-growing piece of musique concrete. At one point, he and

Yoko famously commandeered three separate studios in Abbey

Road (while McCartney recorded “Blackbird” alone in

another), gleefully and artfully mixing tape loops and

recording new passages through the night. The only Beatle

present in those sessions was dry-witted George, who must

have enjoyed the subversive absurdity of taking turns with

Lennon in speaking such random phrases as “financial

imbalance,” “the Watusi,” “onion soup.”

This work, which has few peers in recorded popular

music (see: Frank Zappa), and easily holds its own with

“serious” pieces by avant-garde composers such as Edgard

Varese and Karlheinz Stockhausen,* spurred the first of

several nasty “white album” spats between the two highly

creative, talented, impassioned young Beatles. As Emerick

revealed, when John proudly played “Rev. # 9” for Paul, the

response was an underwhelming, “Not bad”---sending Lennon

into a tirade about how avant-garde music was what

The Beatles should be doing, and that “#9” should be the

band’s “next bloody single!” (Now, that would have been

fun.) One wonders if the subsequent, seemingly endless takes

of Paul’s “Obla-di, Obla-da,” which drove the other Beatles

nuts, were, in part, McCartney goading his estranged writing

partner. (That song was the cause of a very colorful

confrontation in which a heavily stoned-on-heroin Lennon

burst into the studio, pounded a fanfare on the piano,

declaring, “This is how the fucking song should go!” And

that became the

piano intro.)

So the importance of

“Revolution 1-A” is immense. It not only spurred the

creation of “Revolution 1,” “Revolution,” and “Revolution #

9,” but it helped to define the increasingly divergent

musical priorities of Lennon and McCartney at a critical

and transformative moment in the band’s career.

Why it was not later

included on “Anthology” is unfathomable, unless it was a

casualty of too many cooks---or held back for a

future release (a bonus track on the forthcoming remastered

albums?) There is simply no conceivable sound argument

against releasing “1-A” today. What’s more, it is so

important among Beatles recordings that it merits more than

presentation as a “scrap,” outtake, or historical footnote.

It demands formal

production, completion.

I

submit that this song is a compelling, if not irrefutable

argument that whatever remains on Beatles session

tapes---alternate versions, longer takes, discarded

experiments---should not necessarily be released “as is,”

but would often be better served by further production

(preferably by George and/or Giles Martin.) “Revolution

1-A,” for instance, lacks producer Martin’s horn arrangement

and guitar parts by Lennon and Harrison heard in “Revolution

1.” Why not incorporate them into any released version of

“1-A?” Why leave it trivialized as an incomplete outtake? I

would even argue for the inclusion of two tape loops made

for, but not used in the track: all four Beatles singing

“ahhhhh” in upper register, and a manic, high-pitched guitar

figure. The “Anthology,” project, after all, included a

version of “Yellow Submarine” with many more sound effects

than were used on the original version, and discarded spoken

word introduction! (Released on the “Real Love” EP.)

For those who suggest

that such new production work be meddlesome, even

disrespectful of the band or history, there is ample

precedent. Martin and the “Threetles” presided over entirely

new edits and mixes of “Strawberry Fields,” “Here, There,

and Everywhere,” “Yes it Is,” and various other tracks for

“Anthology.” Some of the edits were made to show the

evolution of a song, others stand as solid, viable new

versions in their own right. And then there is “The Beatles

Love,” with its complex and clever mash-ups, some of which

also stand as alternate

versions in their own right: notably the brilliant “Tomorrow Never Knows/Within

You Without You,” and what was effectively an entirely new

Beatles release---the exquisite solo acoustic rendition of

Harrison’s “While My Guitar Gently Weeps,” with brand-new

(and rather magical) orchestration by George Martin. (The

truncated “Hey Jude” also is

a nifty “new” version, with the

neat trick of eliminating all but the “na-na” chorus vocals

during the famed fade-out, then phasing instruments and

orchestra back in.)

“Revolution 1-A” deserves

no less attention. Present it as it might have been, spiffed

up with all parts included. If you’re going to release such

a wonderful rarity, why not give it a proper sendoff?

In

fact, this situation argues in favor of re-thinking the

remainder of The Beatles’ unreleased recorded legacy. Why

think in terms of new releases---albums---being

“Anthology”-like compilations of leftovers, outtakes,

scraps? Why not think in terms of restoration, to the

extent possible? Why not think in terms of a new album or

two--- viable albums that take their artistic places

in the Beatles canon---with reconstructed, embellished,

restored alternate versions of songs? Why not enhance the

legacy in this fashion? Let purists complain. Fans would

love it, and critics would be able to evaluate on the basis

of both historical importance and aesthetic value. Instead

of listening to “what might have been, but wasn’t,” they

will hear “what might have been, and now is.”

Is it possible? Sure. A

scroll through Youtube.com reveals all manner of Beatles

demos that have been “finished”

by well-intentioned amateur

musicians trying to simulate a Beatles sound (as well as

solo Beatles songs with fake Beatles-esque back-up.)

But this is not to suggest anything so

informal or crude, or that new musicians be hired to “play

like the Beatles.” Never. That would be ridiculous. There

are ways to proceed that would preserve The Beatles’ musical

integrity, while adding to the music. The rules: work with

existing materials only, except when George Martin---or a

composer endorsed by the four Apple parties (Paul, Ringo,

Yoko, Olivia Harrison)---is employed to write a new

arrangement.

How successful could such

a venture be? Only a careful listen to the material left on sessions tapes would give a definitive

answer. Yet even without this data, enough is known---from

Lewisohn's book, bootlegs, and leaks---to posit a pretty tantalizing example,

consisting, in this case, chiefly of “white album”-era

recordings. (Dipping, on occasion, into “Anthology” or

“Love” versions, and once into the "Get Back" sessions.)

Call such an album “Off White," or perhaps use either

of the titles rejected by The Beatles for the "white album:""Revolution,"

and "A Doll's House." Use the

cover originally drafted for the "white album," by famed

artist, "Patrick." Here it is:

Child of Nature---This is the famed 1968 acoustic

demo that did not make the “white album” cut---Lennon’s

plaintive, poetic paen to India and meditation (that he

reworked as the inferior, in my opinion, “Jealous Guy,” in

1971.) Paging George Martin! Take one of Lennon’s two lead

vocal lines, isolate it (amateurs have done this on Youtube),

and add orchestration. Voila. Beautiful new ballad.

No, the vocal is not studio quality, but this could work

perfectly well. After all, if Martin’s arrangement for

Lennon’s solo “Grow Old With Me” worked, which it did

beautifully, why wouldn’t this? Sir George has already

orchestrated solo McCartney Beatles songs (“Yesterday,”

“Mother Nature’s Son”), solo Harrison (“While My Gently

Weeps”) and solo Ringo (written by John), “Good Night.” Why

not John?

Hey Jude---There is a fabulous take of the song (not

the one on “Anthology”) that is slightly more brisk than the

released version, with first-rate lead vocal by McCartney

and crisp, sharp drumming by Ringo. It holds its own with

the official version, but lacks harmony and chorus vocals.

Add them from the final version, do some clever phasing out

and in of vocals/band/orchestra a la the

“Love” version, and

you’ve got a substantially different---and

magnificent---version. Lewisohn reports that several fine

takes of the song with Harrison on electric guitar exist,

and they certainly would also merit consideration.

(Especially if Harrison is playing echo-lines, which

McCartney famously rejected, as opposed to rhythm.)

Sour Milk Sea---This is perhaps a dicier

prospect. This Harrison song was written and demoed during

the “white album” period, but then given away to Apple

artist Jackie Lomax, who

recorded it with a band consisting

of Ringo, Paul, George, Eric Clapton, Nicky Hopkins. Remove

the (excellent) Lomax vocal, and substitute George’s from

the acoustic

demo. Would it work? I’ve heard an

amateur

attempt that sounded fair. With studio wizardry, I’m betting

this would succeed. (Doesn’t hurt to try.) And who

knows---maybe there is a studio quality vocal run-through in

the Harrison “vault.”

Goodbye---Do

essentially the same thing with this glorious little Paul

McCartney tune, made an Apple

hit by Mary Hopkin. Paul

produced, arranged, and played on the Hopkin session, so if

you take her vocal off and add his

demo vocal, it’s no

different from other “white album” era Beatles tracks that

featured one Beatle. Would this technically work out? Proof

is in the trying.

I’m So Tired---There is a bootlegged take of this

Lennon song with lots of

echo-guitar lines, presumably by

George, substantially changing the overall feel. It’s great.

While My Guitar Gently Weeps---Not

everyone has heard the

tremendous new version with acoustic

guitar and Martin strings from “Love.” Give it a home among

its peers.

Obla-di, Obla-da---There is an earlier version on

“Anthology 3.” Use that one or one of the other innumerable

takes. For those who despise this song, apologies.

Circles (aka “Colliding Circles”)---Another Harrison

demo for the “white album” that did not make the cut. George

accompanies himself on the organ on this heavyweight

philosophical utterance. Again, calling George Martin (or

Jeff Lynne)! Take Harrison’s vocal, add a touch of

orchestration, a sarod, Indian flutes. . .

Helter Skelter---As is widely known, fans have been

clamoring to hear the nearly legendary 27-minute version of

this song. Well, I differ somewhat with fans here. I’d be

curious to hear 27 minutes of The Beatles raucously

deafening themselves in the studio, but I don’t think I’d

want to hear it often. Cut it to seven or eight---or even

ten---minutes. Give this blockbuster its due. At least

partly. (Make the full version a bonus track.)

All Things Must Pass---There is the lovely, moving

solo studio demo that George performed during the “Get Back”

sessions, backing himself on electric guitar (released on

“Anthology”) that would serve perfectly well here. Sound

quality: excellent. But. . .The Beatles made more than a few

passes at arranging and recording the whole track, including

harmony vocals. Judging from the

bootlegged versions, I’m

betting that with technology and intelligent editing from

these run-throughs and George’s demo, a Beatles version of

the song just might be within reach. Failing that, turn the

Martins loose.

Not Guilty---Yes, there is an edit of the Harrison

song (with fellow Beatles and Clapton) omitted from the

“white album” version on “Anthology,” which is perfectly

spiffy. But there are superior versions on

bootleg. And

can’t something be done to improve the sound quality of

George’s vocal?

Revolution 1-A---Remix, add the horns and guitars

from the “white album” version, plus extra tape loops

initially omitted (see above), and you have one grand

Beatles recording---the hood ornament for this vehicle.

India,

India---A first-rate Lennon ballad, written

during the “white album” period, recorded by John at home at

the Dakota in the late ‘70’s, with acoustic guitar.

Excellent sound quality. (Why didn’t Yoko give this one to

the “Threetles” for a reunion track!) Add George Martin

orchestration, Paul’s bass, Ringo percussion, touches of

Indian instruments, (or combinations thereof) and it’s a

classic.

Savoy Truffle---Harrison has commented in retrospect

that the (terrific) saxophones on this song obscure the

brilliant job being done by the group. Release it,

band-only.

Good Night---Lewisohn reports that the first session

for this song featured Ringo, accompanied on acoustic guitar

by John, with Ringo speaking several little preambles, one

of which went like this: “Come on children! It’s time to

toddle off to bed. We’ve had a lovely day at the park and

now it’s time for sleep.” What a must for release one of

these takes is.

|

The wonderful Patrick cover rejected for the

"white album." |

There are other

possibilities for such an album, including Lennon's solo

acoustic ditty, "Everyone

Hard a Hard Year," and the highly publicized

goof-session of noises, screams, nonsense supervised by

McCartney in ’67, “Carnival of Light” (bonus track!) Another

prospect: take the

acoustic version of “I’m Only Sleeping”

from “Anthology,” and marry it to a loop made of the

vibes

backing track for the song devised by Martin, to create an

entirely new version. Would it work? It does. An

acquaintance has done this in a home studio, and it is

spectacular.

It should be clear by now

that with an open-minded, creative approach, and a

priority of restoration, there is a very fine Beatles album

(or more) that could yet be made from existing unreleased

recordings. There is just no way around this conclusion.

Whether Apple and its four voters have the vision and, yes,

love, to invest in such a project is, as Hamlet said, “a

consummation devoutly to be wished.” And in the end, it

would be nothing short of. . .

Revolutionary.

* Music

critic Richard Ginell agrees concerning the quality of

“Revolution # 9,” pronouncing it the equal or better of any

recognized musique concrete composer in "Third Ear: The

Essential Listening Companion; Classical Music" (Backbeat

Books, 2002).

![]()